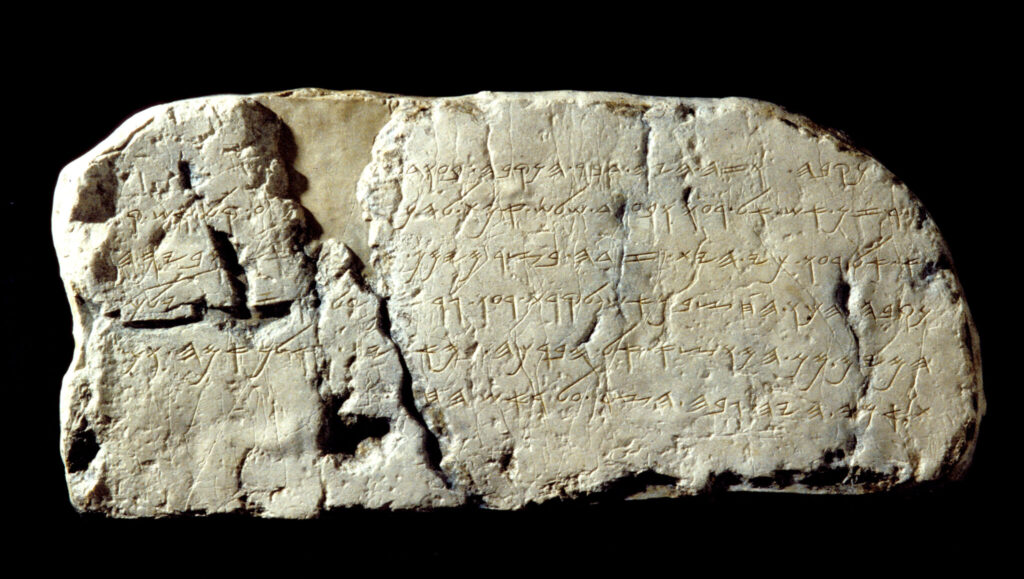

The Siloam inscription, also known as the Shiloah inscription or KAI 189, is a Hebrew inscription found in the Siloam tunnel in East Jerusalem. This tunnel, which brings water from the Gihon Spring to the Pool of Siloam, is a remarkable feat of ancient engineering. But perhaps even more remarkable is the story of the inscription’s discovery by Jacob Eliahu, the adopted son of Horatio Spafford, a man whose life was marked by unimaginable tragedy and unwavering faith.

The Siloam Tunnel and Biblical References

The Siloam tunnel was built during the reign of King Hezekiah in the 8th century BC, as recorded in the Bible. 2 Kings 20:20 mentions Hezekiah’s construction of the conduit and the pool, while 2 Chronicles 32:3-4 describes how he stopped up the waters outside the city to prevent the Assyrian kings from finding much water during their siege.

Jacob Eliahu Spafford’s Incredible Discovery

Despite extensive examinations of the tunnel by Edward Robinson, an American biblical scholar and explorer, Charles Wilson, a British Royal Engineer, geographer, and archaeologist, and Charles Warren, a British Army officer, archaeologist, and writer, during the 19th century, the Siloam inscription went unnoticed until 1880. These three prominent figures were instrumental in the early exploration and study of the Holy Land, conducting surveys, expeditions, and excavations that laid the foundation for modern biblical archaeology.

However, it was not until 1880 that the inscription was discovered by Jacob Eliahu who became the adopted son of hymn writer Horatio Spafford. He was a 16-year-old pupil of Conrad Schick, a German architect, archaeologist, and Lutheran missionary who lived and worked in Jerusalem. Eliahu stumbled upon the inscription while exploring the tunnel, and Schick recounted the discovery in his publication “Phoenician Inscription in the Pool of Siloam”:

“… one of my pupils, when climbing down the southern side of [the aqueduct], stumbled over the broken bits of rock and fell into the water. On rising to the surface, he discovered some marks like letters on the wall of rock. I set off with the necessary things to examine his discovery.”

Bertha Spafford Vester’s Account

Seventy years later, in 1950, Jacob Eliahu’s adoptive sister, Bertha Spafford Vester, shared her own account of the discovery in her book “Our Jerusalem: An American Family in the Holy City“:

“Jacob was above the average in intellect, with the oriental aptitude for languages. He spoke five fluently, with a partial knowledge of several others. He was interested in archaeology, and the year before we came to Jerusalem he discovered the Siloam Inscription…”

She goes on to describe how Jacob, determined to explore the tunnel despite local legends of it being haunted, noticed a change in the chisel marks and felt an inscription on the wall.

The Inscription’s Content and Significance

The Siloam inscription, written in ancient Hebrew, records the construction of the tunnel. The translated text reads:

“… the tunnel … and this is the story of the tunnel while … the axes were against each other and while three cubits were left to (cut?) … the voice of a man … called to his counterpart, (for) there was ZADA in the rock, on the right … and on the day of the tunnel (being finished) the stonecutters struck each man towards his counterpart, ax against ax and flowed water from the source to the pool for 1,200 cubits. and (100?) cubits was the height over the head of the stonecutters …”

This inscription provides valuable insight into ancient engineering techniques and is the only known ancient inscription from Israel and Judah commemorating a public work.

Recent Developments and Current Status

The Siloam inscription has been held by the Istanbul Archaeology Museum since its removal from the tunnel in 1890, following a shocking attempt to steal the valuable artifact. Just 10 years after its groundbreaking discovery by Jacob Eliahu Spafford, a Greek antiquities dealer from Jerusalem tried to make off with the inscription, callously detaching it from the rock wall. During the haphazard quarrying work, the inscription tragically broke into several pieces. Thankfully, Conrad Schick, the very man who had first documented the discovery, had the foresight to create a plaster replica earlier, preserving the inscription’s original form for posterity.

The Ottoman authorities, upon learning of the theft, swiftly tracked down the merchant and confiscated the fragmented inscription and moved it to the Archaeological Museum in Istanbul where it remains to this day. Regrettably, the inscription is not permanently displayed for the public to marvel at and appreciate. Many argue that the rightful place for this remarkable piece of history is, of course, the very spot where it was discovered – Jerusalem. However, despite earnest requests from the Israel Museum to transfer the inscription, even on loan, for the momentous occasion of Jerusalem’s 3000th anniversary celebrations in 1996, the Turkish government has thus far remained unresponsive.

In recent years, there have been several attempts by Israeli officials to secure the inscription’s return, including a tantalizing 2022 report that Turkey had agreed to return the priceless artifact to Jerusalem. However, Turkish officials swiftly denied this claim, stating that since the inscription was found in East Jerusalem, part of the Palestinian territories, it would be inappropriate to return it to Israel.

As of 2024, the Siloam inscription remains in the Istanbul Archaeology Museum, despite ongoing debates about its ownership and significance. The story of the inscription’s discovery by Jacob Eliahu Spafford, a tale of faith, perseverance, and the enduring importance of ancient artifacts in understanding our shared history, continues to captivate scholars and enthusiasts alike.