Born: July 9, 1838, Clearfield County, PA.

Died: December 29, 1876, Ashtabula, OH.

Buried: Chestnut Grove Cemetery, Ashtabula, OH.

Philip Bliss

Hymns by Philip Bliss

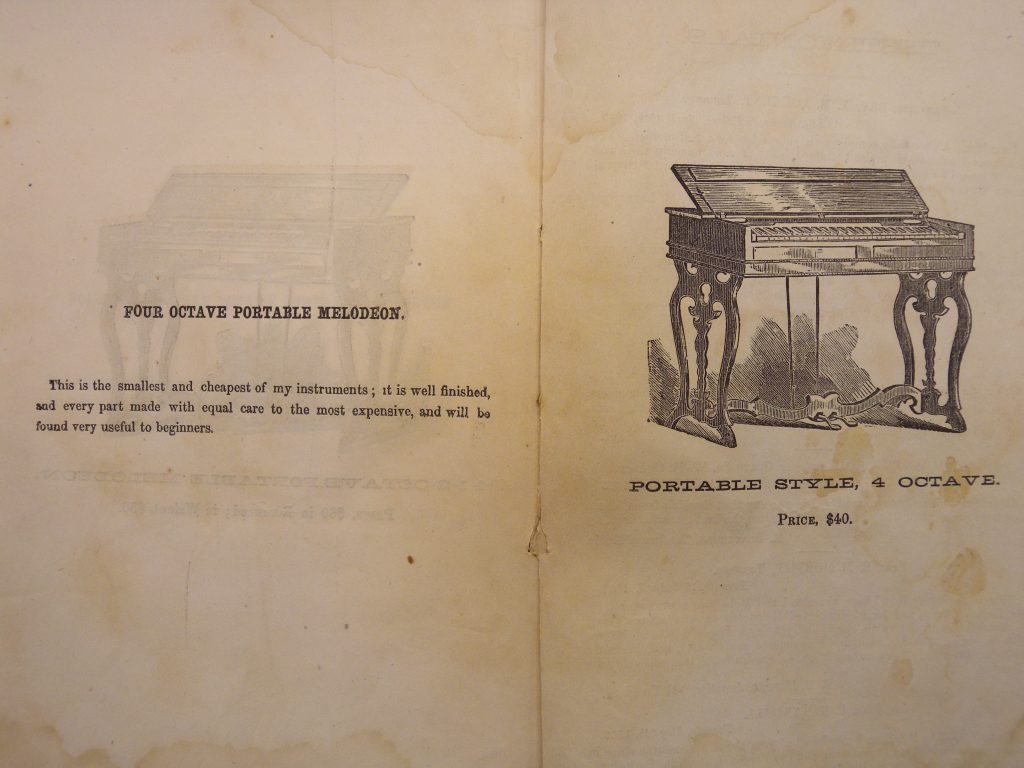

The melodeon was a popular instrument in the 19th century, especially before and during the Civil War era. It’s housed in a piano-like case and is a small reed organ with a five or six octave keyboard.

The Normal Musical Institute

Founded in 1853 by George F. Root, William Bradbury, and Lowell Mason, the Normal Musical Institute was the first school in the United States dedicated to training music teachers. This groundbreaking program offered four-week summer sessions covering harmony, singing, and composition. The institute played a crucial role in shaping the careers of many influential musicians and educators, including Philip P. Bliss, who attended in 1860. Its innovative approach to music education laid the foundation for future generations of American music teachers and composers.

Metropolitan Quartet, 1915

A Hymn That Made History

“I Will Sing of My Redeemer,” words by Philip P. Bliss (1876) with music later supplied by James McGranahan (tune: “My Redeemer,” 1877), holds a special place in early phonograph history. In the months after Edison’s tinfoil phonograph appeared, gospel musician George C. Stebbins made a demonstration recording of this hymn on the new machine and later described hearing his own voice reproduced from the tinfoil. As with nearly all tinfoil demonstrations, no recording survives (playable foils from that era are exceptionally rare and reliably date from 1878 onward) so Stebbins’s account stands as evidence that this hymn was among the earliest known to be sung into a phonograph.

Philip Bliss Home and Museum

The Philip P. Bliss Gospel Songwriters Museum is located in Rome, Pennsylvania, in the house where Bliss lived. Visit their website for more anecdotes and info about Bliss.

A Son’s Musical Journey

The legacy of Philip P. Bliss lived on through his son, Philip Paul Bliss Jr. Orphaned at the age of four when his parents perished in the Ashtabula train disaster, young Philip never truly knew his father. Yet, the elder Bliss’s musical genius seemed to flow through his veins, a striking example of genetics at work.

Initially pursuing ministry, Bliss Jr. graduated from Princeton in 1894. However, music’s siren call proved irresistible, leading him to study under renowned teachers Hugh Archibald Clarke and Richard Zeckwer in Philadelphia, before honing his skills in Paris with Felix Alexandre Guilmant (organ) and Jules Massenet (composition).

Upon returning to America in 1900, Bliss Jr. balanced teaching public school music with his role as an organist in Owego, N.Y. His career took a publishing turn in 1904 when he joined John Church Company in Cincinnati as a music editor, later moving to Willis Music Company and Theodore Presser Company in Philadelphia.

As a composer, Bliss Jr. left an impressive legacy of over 200 piano pieces, numerous operettas, church music, more than 100 songs, solo works for organ, violin and cello, and educational music. A few of his compositions can still be found today.

Bliss Jr. remains a shadowy figure in music history. No photographs of him or recordings of his work have surfaced, despite my sleuthing. Interesting, the only audio fragment of his music I can find is the following video of a theme song for the Owego Free Academy written by Bliss Jr. in the early 1900s. Was this the school where he once taught?

From Humble Beginnings to Musical Mastery

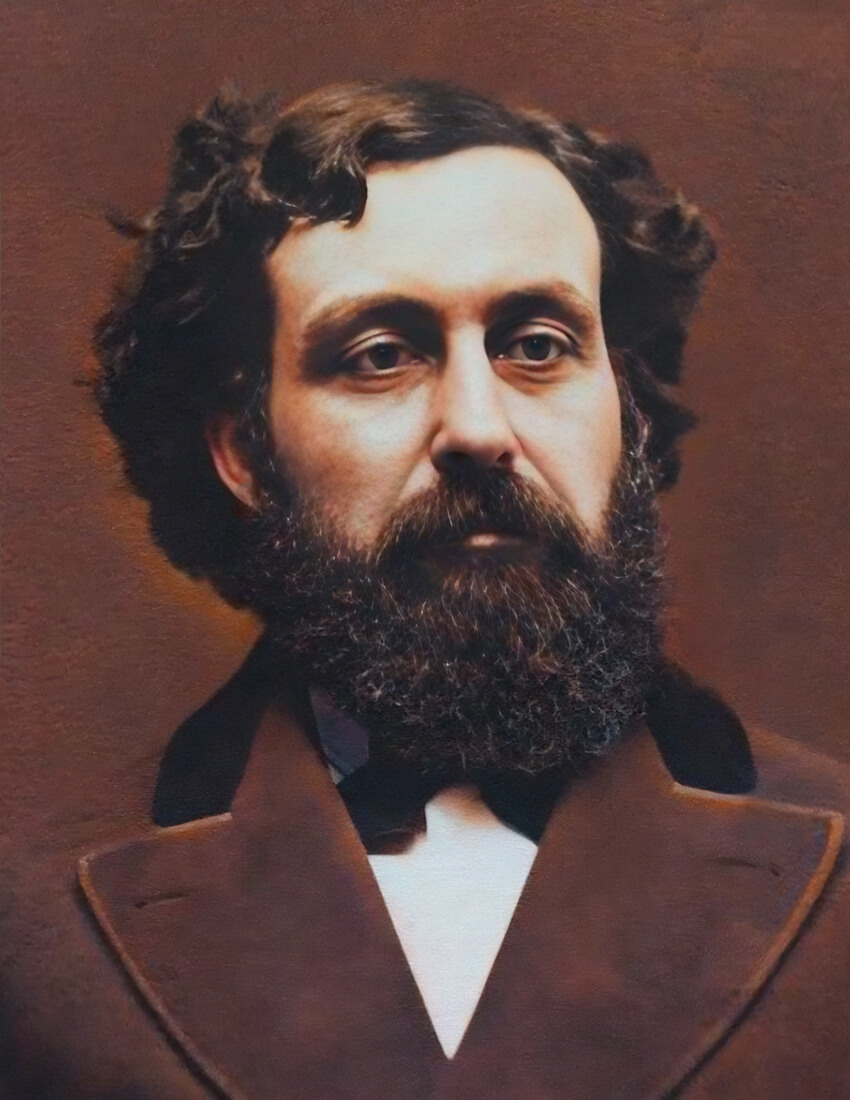

On a summer’s day in 1838, in a modest log cabin nestled in the woods of Clearfield County, Pennsylvania, a child was born who would one day touch the hearts of millions through his music. Philip Paul Bliss entered a world of “abject poverty,” as he would later describe it, but his life would prove to be rich in faith, talent, and impact. Though his life would be tragically cut short at just 38 years of age, Bliss would compose some of Christianity’s most enduring hymns, earning him recognition as one of the most prolific and influential gospel songwriters in American history.

Young Philip’s early years were spent in the rugged environment of farms and lumber camps. He was known as a “large, awkward, overgrown boy,” but beneath his ungainly exterior lay a heart destined for greatness. The Bliss family moved to Kinsman, Ohio in 1844, returning to Pennsylvania in 1847, first settling in Espyville and a year later in Tioga County. In 1850, at the tender age of 12, Bliss made a decision that would shape the course of his life: he accepted Christ as his Savior and joined the Cherry Flats Baptist Church of Tioga County, Pennsylvania.

The Spark of Musical Talent

Even in his youth, Bliss showed an unusual talent for music. But how could a boy from such humble beginnings nurture this gift? A pivotal moment came when Bliss was about ten years old. As he later recounted, he was passing by a house in the village when he heard music sweeter than anything he had ever before encountered. Drawn irresistibly by the sound, the barefoot boy entered unobserved and stood at the parlor door, listening entranced as a young lady played upon a piano – the first he had ever seen.

When she finished playing, the awestruck Bliss exclaimed, “O lady, play some more.” Startled, and with little appreciation for the tender heart so moved by her music, she responded harshly: “Go out of here with your great feet.” Though crushed, Bliss left with the memory of harmonies that seemed to him like heaven, a moment that would inspire his lifelong pursuit of music.

At the age of eleven, in 1849, Philip left home to make a living for himself, spending the next five years working in logging and lumber camps and sawmills. With his strong physique, he was able to do a man’s work despite his youth. In 1851, he became an assistant cook in a lumber camp earning $9 per month. Two years later, he was promoted to log cutter, and by 1854, he had become a sawmill worker.

With determination and faith, Bliss pursued his musical calling. At 17, he completed his requirements to teach and became a schoolmaster at Hartsville, New York, in 1856. When school was not in session, he hired out for summer work on a farm. But it was his meeting with J.G. Towner (father of legendary hymn writer Daniel B. Towner) in 1857 that would truly set him on his musical path. Towner recognized Bliss’s talent and provided him with his first formal voice training. That same year, Towner made it possible for Bliss to attend a musical convention in Rome, Pennsylvania, where he met William B. Bradbury, a noted composer of sacred music who encouraged Bliss to dedicate his talents to the service of the Lord.

A Life Dedicated to Music and Faith

In 1859, Bliss married Lucy J. Young, a woman from a musical family who would encourage and support his talent throughout their life together. Bliss’s own words, recorded in his diary, speak volumes about this union: “June 1, 1859 – married to Miss Lucy J. Young, the very best thing I could have done.” This partnership would prove instrumental in nurturing Bliss’s musical gifts and supporting his eventual ministry. Lucy was a poet from a musical family and a devoted Presbyterian, whose church Bliss joined after their marriage. The couple would often perform beautiful duets together in their service to Christ.

As Bliss’s musical abilities grew, so did his dedication to his faith. He became an itinerant music teacher, traveling from community to community with a melodeon, spreading the joy of music and the message of God.

Bliss’s talent didn’t go unnoticed. In 1864, at age 26, he moved to Chicago and began working with Dr. George Root, conducting musical institutes and conventions throughout the West for nearly ten years. It was during this time that Bliss began to compose hymns that would touch the hearts of generations to come.

A Twist of Providence: The Normal Academy and Grandma Allen’s Stocking

At 22 years old Bliss embarked on a journey that would shape his musical future. Astride his trusty horse, melodeon in tow, he roamed from community to community as an itinerant music teacher. But it was the summer of 1860 that would prove pivotal in his development. The Normal Academy of Music in Geneseo, New York, beckoned – a six-week event administered by renowned musicians that promised to be a transformative experience. Bliss’s heart soared at the prospect, only to plummet when he realized the harsh reality: the $30 fee might as well have been $3000 for all he could afford it.

Enter Grandma Allen, Bliss’s wife’s grandmother, a woman with a keen eye and a generous heart. Noticing the young man’s dejected demeanor, she inquired about the cause. When Bliss confessed the cost, Grandma Allen’s eyes twinkled. “Thirty dollars is a good deal of money,” she mused, before revealing her secret: an old stocking, stuffed with silver pieces collected over years. To Bliss’s astonishment, the stocking held more than enough to cover the fee. “And Bliss spent six weeks of the heartiest study of his life at the Normal,” as the story goes.

The Normal Musical Institute was no ordinary school – founded in 1853 by George F. Root, William Bradbury, and Lowell Mason, it was the first educational institution in the United States dedicated to training music teachers. This groundbreaking program offered intensive summer sessions covering harmony, singing, and composition, playing a crucial role in shaping the careers of many influential musicians and educators.

Who could have known that this simple act of generosity would yield such dividends for the Kingdom of God? Grandma Allen’s stocking full of silver became an investment not just in Bliss’s education, but in the countless lives his music would touch in the decades to come. It’s a poignant reminder that even the smallest gifts, given with love, can ripple outward in ways we can scarcely imagine. Bliss emerged from the Academy with newfound expertise, continuing his itinerant teaching with renewed vigor and skill. Little did he know that this experience would help lay the foundation for a career that would bless millions for over a century to come.

The Call to Evangelism

Between 1865 and 1873, Bliss held musical conventions, singing schools, and sacred concerts under the sponsorship of Root and Cady Musical Publishers. During this time, his reputation as a composer grew steadily, as did his portfolio of hymns and Sunday school melodies, many of which were incorporated into the books The Triumph and The Prize.

One summer night in 1869, while passing a revival meeting in a church where D.L. Moody was preaching, Mr. Bliss went inside to listen. The singing was rather weak, and from the audience, Bliss attracted Moody’s attention. At the door, Moody learned about Bliss’s musical background and immediately urged him to help with the singing at his Sunday evening meetings whenever possible.

In 1870, through the recommendation of Major Daniel W. Whittle, Bliss became the choir director at the First Congregational Church in Chicago. The Blisses moved into an apartment in the Whittle home, and while living there, he wrote two of his most popular hymns: “Hold the Fort” and “Jesus Loves Even Me.” In the fall of that same year, Bliss took on the additional role of Sunday School Superintendent at the church, a position he held for three years.

In 1874, Bliss’s life took another significant turn when he was approached by evangelists D.L. Moody and Major Daniel W. Whittle. They challenged him to enter full-time evangelistic work with them. After much prayer and consideration, on March 24-26, 1874, Bliss joined Whittle for meetings in Waukegan, Illinois, to test this calling. During these services, as Bliss sang “Almost Persuaded,” the Holy Spirit seemed to fill the hall, with many sinners coming forward for prayer and accepting Christ. This experience convinced him, and he made a formal surrender of his life to gospel work, giving up his musical conventions, secular songwriting, business position, and church work to devote himself fully to evangelistic singing.

Bliss accepted the call, and for the next two years, his powerful voice and inspiring leadership became a standout feature of their services. Together with Whittle, Bliss conducted some twenty-five evangelistic campaigns across Illinois, Wisconsin, Pennsylvania, Kentucky, Minnesota, Mississippi, Alabama, and Georgia. His rich bass-baritone voice and his gift for leading congregational singing made him a beloved figure in these meetings.

Bliss’s hymns began to spread far and wide. His prolific output produced some of Christianity’s most beloved songs, including:

“Jesus Loves Even Me” (1870)

“Hold the Fort” (1870)

“Almost Persuaded” (1871)

“Let the Lower Lights Be Burning” (1873)

“Wonderful Words of Life” (1874)

“Hallelujah, What a Saviour!” (1875)

“The Light of the World Is Jesus” (1875)

“I Will Sing of My Redeemer” (1876)

He also composed the music for Horatio Spafford’s “It Is Well with My Soul” (1876) and Frances Havergal’s “I Gave My Life for Thee.”

His talent for composing both lyrics and melodies that spoke to people’s hearts was unparalleled.

A Lasting Legacy

Tragically, Bliss’s life was cut short on December 29, 1876, when the train he and his wife were traveling on plunged into a ravine near Ashtabula, Ohio. The Pacific Express train was struggling through a blinding snowstorm when the bridge spanning the Ashtabula River collapsed, sending eleven coaches plummeting 75 feet into the icy waters below. Five minutes after the crash, fire broke out from the kerosene heaters in the train’s cars. Witnesses reported that Bliss managed to escape but returned to the burning wreckage to try to save his wife, who was trapped under the ironwork of the seats. Of the 159 passengers aboard, 92 perished in what became known as the Ashtabula River Railroad Disaster.

Yet, even in death, Bliss’s music continued to touch lives.

In a twist of God’s providence, the Blisses’ trunk had been sent ahead to Chicago and arrived safely. Inside was a manuscript for “I Will Sing of My Redeemer,” which would later be set to music by James McGranahan. This hymn became one of the first songs ever recorded on Thomas Edison’s newly invented phonograph, preserved by a mixed quartet in New York City around 1877 during a demonstration of this groundbreaking device.

Another of Bliss’s enduring legacies was his tune for “It Is Well With My Soul.” He named the tune “Ville du Havre,” after the stricken vessel that had inspired Horatio Spafford to pen the famous hymn. This connection between personal tragedy and profound faith epitomized Bliss’s approach to his craft.

A Voice That Still Resonates

Professor F.W. Root, who occasionally coached Bliss vocally, paid this tribute to his remarkable voice: “Mr. Bliss’s voice was always a marvel to me. He used occasionally to come to my room, requesting that I would look into his vocalization with a view to suggestions. At first a few suggestions were made, but latterly I could do nothing but admire. Beginning with D-flat below (F-clef), he would, without apparent effort, produce a series of clarion tones, in an ascending series, until having reached G space above (C-clef) with pure tone.”

George C. Stebbins, a fellow hymn writer, paid tribute to Bliss’s unique gift:

“There has been no writer of verse since his time who has shown such a grasp of the fundamental truths of the gospel, or such a gift for putting them into a poetic and singable form.”

This talent for distilling complex spiritual truths into accessible, emotional lyrics is why Bliss’s hymns continue to resonate with congregations worldwide. His songs speak to the universal human need for a Savior, offering comfort, hope, and inspiration to generations of believers.

Throughout his career, Bliss published several notable collections, including The Charm (1871) for Sunday schools, The Song Tree (a collection of parlor and concert music), The Sunshine for Sunday Schools (1873), The Joy for conventions (1873), and Gospel Songs for gospel meetings (1874). After the great success of his evangelistic work with Moody and Whittle, Bliss compiled Gospel Songs, which brought in royalties of $30,000 – all of which he donated to support evangelical work.

After Ira Sankey returned from Moody’s campaigns in England, Bliss and Sankey combined their respective works into Gospel Hymns and Sacred Songs in 1875, which became immensely popular and influential in shaping American church music for generations to come.

From the lumber camps of Pennsylvania to the grand stages of Chicago, from the pages of hymnals to the grooves of Edison’s early recordings, Philip P. Bliss’s journey is a symbol of the power of faith, talent, and perseverance. Though his life was tragically short, his legacy lives on in the countless voices that still sing his words today:

I will sing of my Redeemer,

And His wondrous love to me;

On the cruel cross He suffered,

From the curse to set me free.

As we reflect on Bliss’s life and work, we’re reminded that our own voices, however humble, can touch hearts and change lives when raised in praise and devotion. Philip P. Bliss’s story continues to inspire us to use our gifts, whatever they may be, to spread joy, hope, and faith to all who will listen.

Historical Connection: Bliss’s Hymn and the Titanic

A remarkable testament to the enduring impact of Bliss’s music comes from the survivors of the RMS Titanic disaster in 1912. Multiple survivors, including Dr. Washington Dodge, reported that passengers in lifeboats sang Bliss’s hymn “Pull for the Shore” while rowing away from the sinking ship.

During a luncheon talk at the Commonwealth Club in San Francisco on May 11, 1912, just weeks after surviving the tragedy, Dr. Dodge recounted: “Watching the vessel closely, it was seen from time to time that this submergence forward was increasing. No one in our boat, however, had any idea that the ship was in any danger of sinking. In spite of the intense cold, a cheerful atmosphere pervaded those present, and they indulged from time to time in jesting and even singing ‘Pull for (the) Shore’…” This poignant connection between Bliss’s music and one of history’s most famous maritime disasters shows how his hymns provided comfort and hope in humanity’s darkest moments, even decades after his death.

Postscript: Bliss’s Son George Died On Same Day and Month Years Later

Published in the Harrisburg Telegraph (Harrisburg, PA) – July 18, 1938

Massed Choir of 500 Voices Lead in Reviewing Works of P. P. Bliss

Rome, July 18 (AP) – Thousands of persons, representing many states of the union, gathered in a boiling sun in this little village yesterday to honor the memory of P. P. Bliss, internationally known composer, born 100 years ago.

The throng, massed about a raised platform near the cemetery where the Bliss cenotaph stands, sang the words of his famous “Let the Lower Lights Be Burning,” “Wonderful Words of Life,” “Hold the Fort,” and many others. Hymns echoing over the hills where Bliss in his young manhood taught the old-fashioned “singing school.”

Homer Rodeheaver of Billy Sunday campaign fame led the massed choir of 500 and the huge congregation in the singing while the principal address was delivered by Dr. Will A. Houghton, president of the Moody Bible Institute, Chicago.

On the platform were the widows of Bliss’ two sons, Philip Paul Bliss, Jr., and George Goodwin Bliss. Mr. P. P. Bliss, Jr., said both sons died in 1933, George in the same month and on the identical day on which his parents were killed in the railroad disaster at Ashtabula, Ohio, in 1876.

George C. Stebbins of Catskill, N. Y., composer of “True Hearted, Whole Hearted,” “There Is a Green Hill Far Away,” and other gospel hymns, and a personal friend for years of Mr. Bliss, sent greetings through John R. Clements of Binghamton, N. Y., president of the Billy Sunday Club of that city. “I would love to go to Rome to express my regard for the memory of Mr. Bliss,” he wrote, “if it were at all possible with my 92 years of age. Aside from the deep friendship for him beginning in 1870—a friendship which I have greatly treasured, I have held him in high honor as a man of rare mental and spiritual attainments as well as his possessed unequalled gifts. It has always seemed to me, as a writer of unapproachable evangelical songs.”