Born: February 27, 1807, Portland, ME.

Died: March 24, 1882, Cambridge, MA.

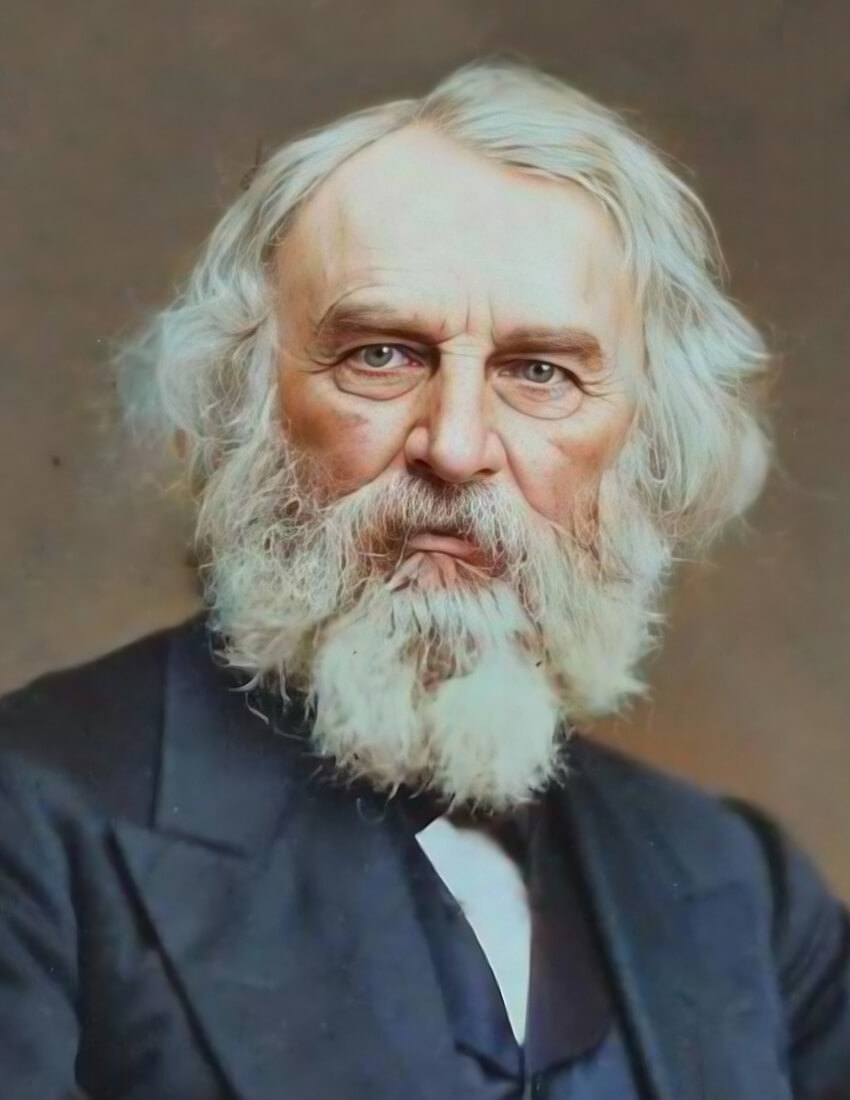

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow

Hymns by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow

Does talent guarantee happiness? Can success shield us from life’s deepest sorrows? On July 9, 1861, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow awoke from a nap to find his beloved wife Fanny’s dress engulfed in flames. His desperate attempts to save her left him severely burned, and she died the next morning. The tragedy struck America’s most celebrated poet at the height of his fame, proving how even the most lauded figures face trials that shape both their character and their craft. Longfellow knew both the heights of acclaim and the depths of personal tragedy, weaving both into verses that still move readers today.

Wadsworth’s Early Life, Education and Literary Beginnings: From Portland to Bowdoin College

Born in Portland, Maine on February 27, 1807, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow emerged from a background of privilege and possibility. His father Stephen practiced law, while his grandfather Peleg Wadsworth had fought as a general in the Revolutionary War. Young Henry showed his literary inclinations early, publishing his first poem in the Portland Gazette at just thirteen years old. This wasn’t mere childhood dabbling – Longfellow burned with ambition, writing to his father during his college years, “I most eagerly aspire after future eminence in literature, my whole soul burns most ardently after it.”

Bowdoin College shaped Longfellow’s early adult years, where he formed a lifelong friendship with Nathaniel Hawthorne and graduated fourth in his class. The college trustees, impressed by his abilities, offered him a professorship in modern languages – with one condition. He would need to study abroad first, a requirement that launched him on a three-year European journey that would profoundly influence his literary perspective.

First Marriage and European Travels: Mary Potter Longfellow and Academic Career

Mary Potter entered Longfellow’s life as more than just a childhood friend from Portland – she became his first wife in 1831. The young couple settled in Brunswick, Maine, where Longfellow taught at Bowdoin. Their happiness, however, proved fleeting. During a second European trip in 1835, Mary suffered a miscarriage while they were in Rotterdam. She never recovered, passing away at just 22 years old on November 29, 1835. Longfellow’s grief poured onto paper: “One thought occupies me night and day…She is dead – She is dead! All day I am weary and sad.”

Romance and Persistence: The Seven-Year Courtship of Frances Appleton Longfellow

Longfellow’s heart would be stirred again when he met Frances ‘Fanny’ Appleton, daughter of a wealthy Boston industrialist, while traveling in Switzerland. The poet fell deeply in love, but Fanny proved decidedly uninterested in marriage. What followed was a seven-year courtship that tested Longfellow’s patience and persistence. “Victory hangs doubtful,” he wrote to a friend. “The lady says she will not! I say she shall! It is not pride, but the madness of passion.”

Longfellow’s determination manifested in daily walks across the Boston Bridge from Cambridge to Beacon Hill, where Fanny lived. His persistence finally paid off on May 10, 1843, when Fanny’s letter of acceptance arrived. Too excited to wait for a carriage, Longfellow walked 90 minutes to meet her. They married, and Fanny’s father gifted them the Craigie House in Cambridge – George Washington’s former headquarters during the Revolutionary War.

Tragedy Strikes Again

The Longfellows built a beautiful life together, raising six children in their historic home. But on July 9, 1861, tragedy struck with shocking swiftness. Fanny was sealing an envelope containing locks of their children’s hair when her dress caught fire. Longfellow, awakened from a nap, tried desperately to save her, suffering severe burns himself in the process. Fanny died the next morning, leaving Longfellow so devastated he feared for his sanity, writing, “I am inwardly bleeding to death.”

The Civil War Years and “Christmas Bells”

Personal tragedy wasn’t all Longfellow endured. The Civil War brought its own sorrows when his son Charles, or “Charley” – whom Longfellow dubbed his “enfant terrible” – joined the Union Army against his wishes. Always one for mischief – he had already lost his left thumb in a gun accident at age eleven – Charley secretly fled home to enlist in the Union Army. Despite his missing digit, he earned a commission as a cavalry officer in the First Massachusetts Cavalry Regiment and gained a reputation as a crack sharpshooter. But in November 1863, Charley was severely wounded, the bullet missing his spine by inches. It was against this backdrop of personal pain and national strife that Longfellow wrote “I Heard the Bells on Christmas Day,” a poem that moved from despair to hope.

America’s Poet Laureate: Literary Achievement, Translation Work and Later Years

By the time of his death in 1882, Longfellow had shaped American literature in profound ways. His poems like “Paul Revere’s Ride” and “The Song of Hiawatha” had become part of the nation’s cultural fabric. He was the first American poet honored with a bust in Westminster Abbey’s Poets’ Corner, and his 70th birthday was celebrated almost like a national holiday.

Yet perhaps Longfellow’s greatest legacy lies not in his accolades but in how he transformed personal suffering into verses that still comfort readers today. His poetry reminds us that even in life’s darkest moments, hope persists – much like the Christmas bells that inspired his famous carol, ringing out their eternal message of peace.

His life stands as proof that great artists aren’t immune to suffering, but rather channel it into works that help others navigate their own trials. As Longfellow himself wrote in later years, “Something remains for us to do or dare; even the oldest tree some fruit may bear.”